|

|

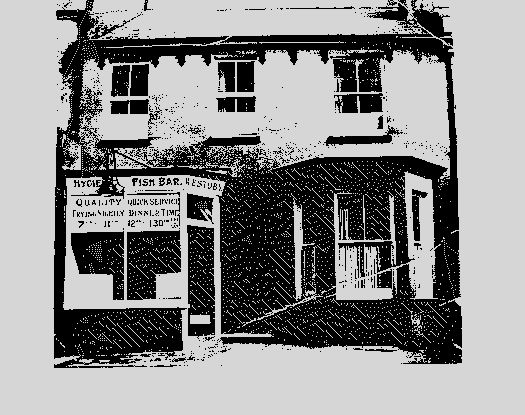

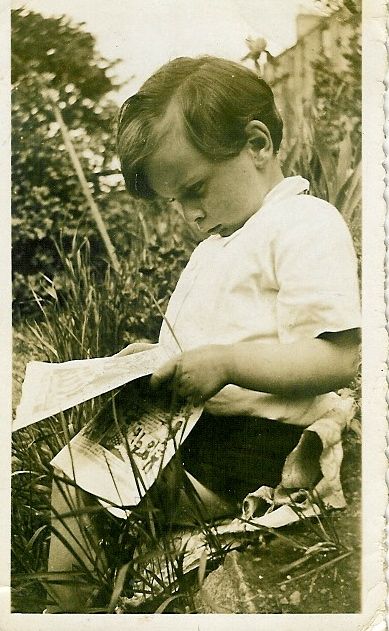

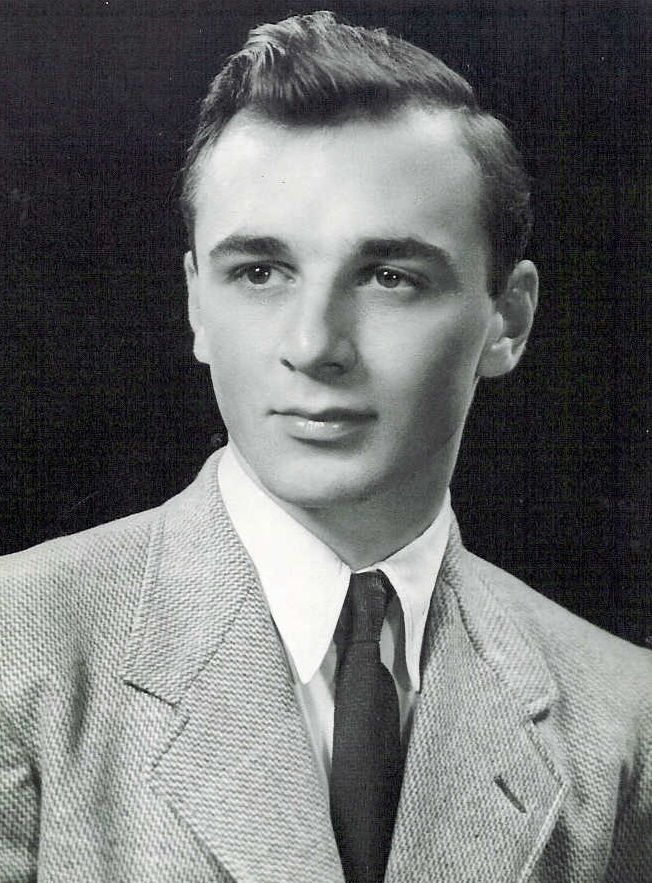

But why not start at the beginning? I was born on 16th May 1932 in a nursing home on Hunny Hill, at Newport in the Isle of Wight. My mother, Ivy, nee Barker, was 38 years old and my father, George Westoby, 51. I guess I was a surprise, since my brother George was already 11. I was christened Alfred Jonathan, but no-one at home ever called me anything but Jon and now everyone who knows me does so too, mostly because I fought kids who called me "Johnny" and old habits die hard. I was named after each of my grandfathers, and never met either! My father owned a fish shop in Newport at the time and my mother helped in the shop. She had two girls to help in the house, Joyce and Vi. Vi had been engaged - as was the country custom then - eventually for about 15 years to Ron Etheridge. They pushed me in my pram and most people thought I was their child until we moved to Hastings in 1937. | ||||||||||||||

|

Hastings | ||||||||||||||

Joyce came with us but Vi stayed behind and married Ron. It was to be another 11 years before they had their own son. One of my early memories is receiving from them on my birthday (5 or 6?) a wooden crate, which proved to contain a pedal car with battery operated lights. Hastings is hilly, so the pedals often whizzed round by themselves, while I concentrated on the somewhat erratic steering!

This first seven years of my life have sheltered me ever since, hence the title. I had parents who were fond of me, two young women who spoiled me and an older brother who was more like a kindly uncle. When I was two, he bought me a full sized trike with chain drive out of his own pocket money. My mother worried that he would be upset because, of course, I couldn't ride it, but my father turned it upside down and I'm told I spent many happy hours whizzing the wheels round by turning the pedals by hand. Is this why I've always been interested in engineering? I only remember some of the detail, but the idea that people are good-natured until proved otherwise has stayed with me ever since. Before I was born, my brother George fell ill and my mother took him on holiday to convalesce, leaving my father to look after himself. This must have been before the advent of the sisters who worked for us. My mother returned to find that Dad had coped with washing up everything but the saucepans (soda and elbow grease removed cooking fat in those days). Every pan in the house was dirty - and that included the new set he'd bought when he had dirtied the old ones! I guess household chores were chores in those days; vacuum cleaners a rarity, open fires with dirty grates and dirtier chimney sweeps, the washing done all Monday with a copper boiler, a posher (a hand operated tool for agitating the clothes and water) and a mangle. The mangle was BIG and stood outside in the glass-covered, whitewashed yard. 3 ft long wooden rollers pressed together with a leaf spring and turned by a 2 ft diameter cast iron wheel could squeeze nearly all the water out of double sheets folded in half, with the water running out of a hole in a wooden trough below the rollers. It also could surprise the cat, especially when it stuck its tail up through the hole and had the end wound into the rollers. A howl, a lifted sheet to reveal the cat suspended, a rapid reversal of the handle and an equally rapid retreat by the cat. We didn't see it for three days and thereafter it always had a kink in its tail. Mondays always smelt of wet washing and cabbage. A mains radio was big and made of wood and bakelite. Only the very rich had a radiogram and that was a floor-standing piece of furniture. We had a wind up gramophone that played 78 rpm records using steel needles or rose thorns. My father ran his business without a telephone, as did most of his contemporaries. I was the first in our immediate family to have a phone, in 1957.

For three years my father prospered in Hastings in a modest way but, over my head, world events were moving to a climax. My brother, at 17, had joined the Territorials, much to my parents' dismay. On the outbreak of war, he was sent immediately to France in the 7th Sussex regiment and was posted missing some days after Dunkirk in an action which halted the German advance for the first time. We subsequently found that he must have been killed in that action but, until my mother received a photograph of his grave, she kept alive a spark of hope, questioning returning prisoners of war for news and writing to any organisation that helped trace missing soldiers. Until death entered my adult life, I did not realise how necessary it is to bury your dead and mourn; grow through the grief and live on. My parents must have suffered deeply and, as far as I was concerned as a child, in silence. As for me, I could not really comprehend my brother's death. Later, after my father died, my mother told me that I had never really known him as she did; that George's death had changed him radically. In fact, it was in that year, when I was 7, that our lives were changed, for better or worse, irrevocably, for in 1940 France fell to the Germans and England was about to be invaded. Hastings was evacuated, adults as well as children, and became a ghost town. Hoping against hope that my brother would return, and needing to nurse the business, my parents sent me away and stayed, but as hope faded and, when one day's takings amounted to two old pence, they too left for Somerset and Joyce returned to the Isle of Wight. We had lived on West Hill and some of my schoolmates were from the old town, the sons and daughters of fishermen. They enjoyed a vocabulary strange to me and one of the very few times my mother clumped me was when I surprised her, aged about 6, by asking what "fuck" meant. She didn't tell me, either. Another experience, maybe at 5, was being told in school about God. My parents were nominal C of E, because everyone without strong religious convictions was assumed to be, but they didn't tell me much about religion, just instilled Christian-like morality into my behaviour. At school, however, some teacher told me I had to be good, because God was watching me all the time and writing my behaviour down in a big book. Even at 5, I didn't believe her and, secondly, it seemed a poor reason for being good rather than bad. Where's the virtue in being good if you only do it while you're watched? To me, good was good because it felt good. If bad felt good . . . but what do 5 year olds know? More later. One early memory was of being taken to the dentist and raising hell when he tried to give me an injection. Another, far pleasanter and much more fascinating was when my mother went shopping at a sort of haberdasher cum clothing shop. The cashier there sat in a glass fronted box high up in the shop with wires leading to every counter; money was put into little trolleys which tinged, then shot upwards as if by magic to be cashed and returned with change. I also had a 'stick with an 'orse's 'ead 'andle', to paraphrase Stanley Holloway, and stood on the bed to hit the lampshade with it. I fell off the bed, hitting the wardrobe and fracturing my left forearm, which had to be put in a sling. This was the month I started school and I learned to write etc with my right hand. I had previously been left-handed and I still do some things left-handedly. My left eye is my master eye. Being a bit ambidextrous can be quite useful. I also liked climbing the sandstone cliffs on East Cliff, which had (and has) a funicular railway from the fishermans' old town to the top. It was especially exhilarating in winter, when the Channel gales threw waves and shingle over the front. Children played in the street and in each other's gardens with very few toys, but lots of imagination. With a single steel pole and a muddy patch, two of us started to dig to Australia. We got quite a way down, but gave up when we didn't strike daylight at the bottom. We could also sit in the gutter on very hot days popping the tar bubbles the sun created, or on wet days, sailing paper boats down the rushing water to the drains. We got pretty wet and dirty but I cannot remember that anyone cared. | ||||||||||||||

|

My father, at this time, had a very strange vehicle. It was a three-wheel motorbike. The front wheel had been substituted by a zinc-lined insulated box on two wheels, steered by a bar at the back of the box. My father would collect fresh fish from the local market in this thing and one day he came off it to be brought home on a ladder with a long cut on his forehead and concussion. When the doctor applied iodine, he exclaimed, "Ee bah goom, that bloody hurts!" He hadn't spoken with a Yorkshire accent for 30 years. He taught me to read before I went to school and read to me as well. I do remember being curled up in his lap, being read to and following the words as best I could. I rapidly grew out of infant texts and by 7 was reading William books to myself - only half-comprehended, but wholly absorbing. Our surname, Westoby, is an anglicised version of a Viking (Danish) name meaning "west of the village". Whether that was downwind or not, I don't know, but lots of us seem to have rowed across to Lincolnshire and Yorkshire, hit the local farmers' daughters over the head and settled down. Someone once wrote to me saying she had been born a Westoby and that there were only 200 families of that name, however you spelled it. She was going to research them all in her retirement, but I never heard from her again. My father was estranged from his family in Hull and I knew nothing about them in his lifetime, but I later found his a solicitor’s invoice re his father's will, which showed he shared with his two brothers and two sisters an estate of three houses. My father's share came to £84.

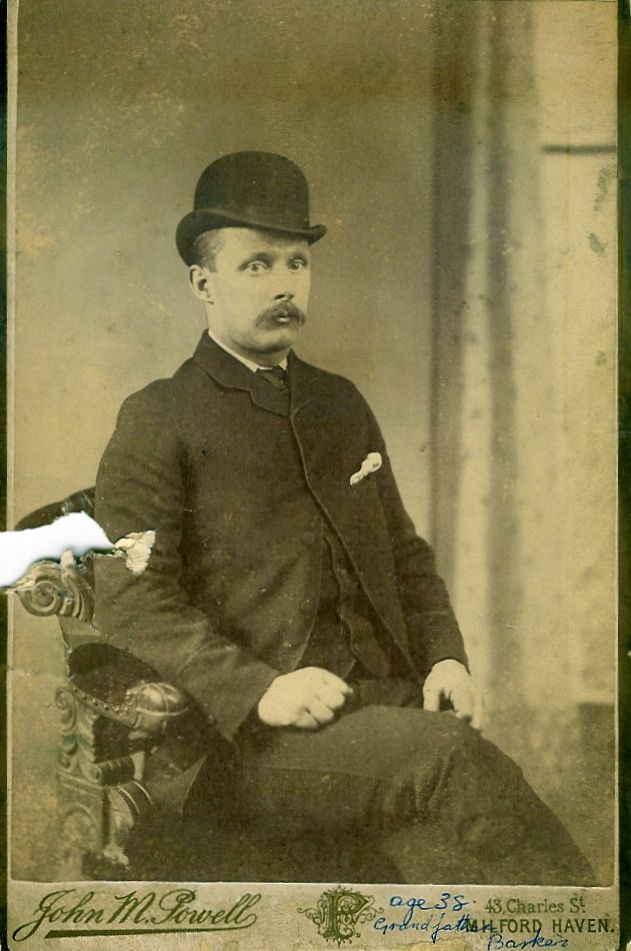

I know more about my mother's side of the family, the Barkers. Her father was a trawler skipper out of Grimsby and she was the youngest of seven children. After her mother died, her father married again. While he was at sea, the stepmother beat the children, all of whom left home one by one until my mother was the only one remaining. She was often kept home from school to look after her two baby stepsisters and be beaten with a piece of rubber hose, threatened with dire consequences if she told the school inspector or her father and generally made miserable, until she left to go into service in Derbyshire.

At 18 or 19 she shinned down the drainpipe and eloped with my father, who was 13 years older. They moved to the South coast and my father managed a series of fish and chip shops before starting his own. My mother had a little girl who died in infancy while my father was serving in the first World War He remained alive by catching shingles. He was in hospital when his battalion went back to the line and was one of only a handful of survivors. The brasshats didn't want to put them with other untried units because of the terrible tales they could tell, so he spent the rest of the war guarding prisoners, learning German and matriculating. After the war, my parents picked up the pieces of their lives and in 1921 my brother George was born. My father painstakingly built up his business again in the Isle of Wight. In those days tourism for the masses was unknown and my parents were "overners" - people from over the water. They remained overners - although with many good friends - until the day they left. Tradition and inbreeding abounded. Many families had someone "under the Clock" - the clock was in the tower of the local mental institution at Carisbrooke - and Queen Victoria had a house, Osborne House, at Mottistone. Even after Queen Elizabeth had ascended the throne, you could never be sure which Queen an elderly islander was referring to, until the context made it clear. | ||||||||||||||

|

Meanwhile, I had been evacuated with my school to Welwyn Garden City, a town that had already seen an influx of evacuees from the East End of London come and go during the 'phoney war' in 1939. That experience soured many residents and billets were hard to find. With a name like Westoby, I was last in line. I just remember a very long day, with two volunteer women (and me in tow) being turned away time and again. Eventually, I'm sitting on a doorstep, kind of tired, while adults argued my fate over my head. A little Scottie dog came out to be friendly and I petted it. "He likes the dog," someone said, "All right, we'll have him." That was in Barnfield Road, maybe No 28?

I was seven, armed with 'William the Bad', a toy pistol and a luggage label identifying me. Two toys were our ration. I cried a bit in my camp bed that night, but no-one noticed. However, my previous experience with grown-ups was all good. I had every expectation of being treated properly and I reckon I was. Whether my mother would have agreed, had she known the full extent of my freedom that summer, is a different matter. The 'adults' in charge of me were, in fact, two teenage sisters married to soldiers who had immediately been posted abroad. They had set up house together and what they knew about cooking and child management between them could have been written on a postage stamp without obscuring the King's head. Boiled eggs with curry powder was a staple. It was years before I attempted Indian food. I found friends and went out with them at weekends - all day. I'd come back at 6 or 7 o'clock and the sisters would say, "Had a nice day?" And I had. No harm came to me except cuts and bruises and I learned self-reliance and independence. Today, I think of myself as a liberal (with a small 'l') and am mostly against censorship. I can't help wondering, though, if many troubled young children know too much. Looking back, I believe I and my companions were somehow protected by our innocence from the undoubted perils that surrounded us. Many of the police, gamekeepers and responsible adults had disappeared into the armed forces. We roamed freer than any middle-class child would today. The woods did contain prowlers who tried to strike up incomprehensible conversations and lovers whose antics were equally uncomprehended, but were a source of interest, amusement and flights of ignorant fancy. I had to reach puberty before that interest became prurient and then I was much more interested in trying out than watching! Our major sins were smoking cigars stolen by one boy from his father or, more disgustingly, dog-ends from the gutter, and scrumping apples to disguise the smell (and to tell the truth, the taste!) Between the ages of eight and fifteen, boys went around together; girls were excluded. Occasionally we might show off by fighting, shouting or swaggering in front of a pretty sister, but we were really into adventure. The Garden City had its own abandoned gravel pit and brickyard, where the Gosling Stadium now stands. The Home Guard had turned it into an assault course, where we naturally assaulted each other. I recall being caught by a rival gang and stuffed down a barbed wire filled trench and peed on. I don't think that was part of the standard Home Guard training! It was also a rifle range and a source of live ammunition. We discovered that cordite burned without exploding outside the cartridge case, but putting a bullet in a vice and hitting the detonator with hammer and nail wasn't a good idea. Newspaper soaked in weedkiller and sealed in a steel tube made a dangerous bomb and why nobody I knew was killed is a mystery to me. Cuts and bruises were commonplace (my knees were always scabbed), but we all thought ourselves immortal. The abandoned workings included a narrow gauge railway running down into the pit. By propping the broken rails on drums, we engineered a braking slope and, Sysiphus-like, endlessly pushed a little wagon to the top, leapt in, overflowing the sides, and entrusted ourselves to gravity and luck. Even today, when my feet get entangled in the bedclothes, I awake with a start from a dream of hurtling down a chute from which there can be no escaping the crash at the bottom. The road down into the pit was cut through high banks and spanned by a water pipe; 30 feet above the roadway in the middle and maybe 30 feet from side to side. We shinned across this, sloth-like with our arms pulling out of their sockets. Extreme fear kept our hands closed when physical strength gave out! Close by was the Twentieth Mile Bridge with an outward sloping parapet protected by two strands of barbed wire. Walking on the roadway was dull, so we walked on the parapet outside the wire or, for variety, on our toes on the semicircular decoration on the outside wall of the bridge, holding on to the parapet with our hands. Remembering what we did, I used to worry about my own sons when they were out, since I didn't expect them to be any different and I reckon we grew up by the 'Grace of God and the turn-up'. The brickworks bridge, long gone, was deserted and just the place to stand and try to drop half bricks down the smokestacks of trains passing underneath. We trespassed on the railway lines and stokers hurled lumps of coal at us. We put pennies and ball bearings on the lines; the first got flattened and the second drove wiggly channels along the relatively soft metal of the rails. On the Hertford line, little used, we found snakes and lizards under the corrugated iron sheets by the rails and took them home as (very temporary) pets. When my mother finally caught up with me by visiting, staying and telling my Dad he'd better come too, she thought I'd become a street arab. I guess she was right. I'd come from an infant school and was put into the toughest junior school (in Peartree Lane) in the town. I didn't know any swear words or common nouns for rude parts of the body and I was wearing shoes. Such was the need for protective camouflage that I spoke 'ertfordshire at school and middle class Hampshire cum Yorkshire at home. I used to write to my mother begging for boots so I could be like the others and maybe kick back. In self-defence, I joined a gang (get the strength of a gang around you) and life improved. I used to have breakfast and go to the gang leader's house to go to school with him. There I was given fried bread, a welcome piece of junk food. I was an adult before I realised I'd been sharing a poor family's only breakfast. They also used to give me 'bacon bones', thin rib-like bones that could be chewed for the marrow. In war-rationed Britain, better than sweets! Rationing - very small portions, unless you knew a black marketeer and had money. 2 ounces of butter per week was just a scraping on bread, so I mostly had dry bread and jam and saved enough butter that way to have at least one slice thickly covered. The dripping from beef was favoured as a coating for bread, especially with the brown jelly at the bottom of the bowl, liberally sprinkled with salt. Incredibly unhealthy by today's lights, but such items were so small and distantly spaced, they were necessary treats in a dull but healthy diet. So there I was in Welwyn and, after almost two years, my parents joined me in lodgings. They both got jobs and, at the end of the war, a place to rent, No 4 Heather Road. My father retreated into his books and a certain silence. My mother worked in a shop and found new friends in this new town. Ours was a mother-centred family. She did the day-to-day discipline and if my transgressions merited intervention from the 'old man', I was in trouble indeed. It didn't often happen and its rarity meant that he didn't shout or bully. One quiet reprimand and a straight look kept me walking circumspectly until I was in favour again - never a long process! An old Chinese curse is "May you live in interesting times" and certainly what interests historians can be exceedingly uncomfortable to live through. Surviving it, however, does provide for memories to enliven an old age. From working with horses on farms and drawing drinking water from a well, I've lived through a world war to see the electronic age, Concorde, men standing on the moon and a new understanding of our origins and morals. Air raids were a way of life and every holiday, summer and winter, I would be sent to our friends in the Isle of Wight "to get away from the bombs". The viaduct with 2 rails leading North was a constant target, as was De Havilland aerodrome in Hatfield. That was camouflaged, and Panshanger airfield exposed as a substitute – very successfully – it was bombed 44 times! Previously, the latter had been the training base for 400 Battle of Britain pilots and much later, a training site for jet pilots on Chipmunks. Little did my mother know of radar and the big aerials at Ventnor - a constant target for the bombers. I didn't tell her. I enjoyed the holidays on the farm too much. Mostly, I travelled by myself to Portsmouth and the ferry, being met at Ryde by my hosts. Our Island friends were Vi and Ron. Ron was the carter on the farm. He was a highly skilled man. Carter and vet, ploughman, mender of harness and gear, thatcher, corn rick maker and, at a pinch, cowman, he turned his hand to every task on the farm. He needed to; too few men and no diesel meant the tractors were laid up and horses came into their own again. Two shire horses worked as a pair and I have walked behind them learning to plough, harrow and reap. Before the reaper could get onto the field, we had to scythe the first swathe, make and stook the sheaves, then continue behind the reaper, stooking the corn (five sheaves to a stook) to dry it. To make a sheave - grab an armful of corn stalks and wrap a twist of stalks round it. To make a stook, pile five sheaves in a wigwam shape, jamming the heads together. There was always a shotgun riding the reaper and a couple of hands with their dogs waiting for the rabbits to bolt from the last patch of standing corn in the middle of the field. After several days, the drying sheaves were thrown by pitchfork into a horse-drawn hay-wain that Constable would have recognised immediately and, when I tired of forking or stacking on the wagon, I was allowed to drive it. Long, gradual turns were needed; I was warned it was all too easy to overturn - although I never saw it happen. The corn rick was built to a traditional design, with all the sheaf heads inwards, tunnels left in the rick so that heat did not build up and cause a fire, then thatched with bright straw and willow pegs, until the corn was dry enough to thresh and store in the granary. I was taught to do this. I wish I could say I remember still. Why are childhood days always sunny? I remember stopping for "nammet" - lunch to you - dropping into a soft hedgerow in the sun, eating my sandwiches and sharing a bottle of cold, sweet, milkless tea with my mentor, Ron. Sometimes I would be sent to the Barley Mow in Shide for bottles of beer that mine host had not the slightest hesitation in selling to me (aged 9 to 12). I took the horses to town as well - always under supervision. The cattle truck was a slatted rail, open "buckboard" with a narrow wooden seat behind the horse and right up against the slats. The first time I drove the young bull calves to market (understanding they would be sold for slaughter), I felt sorry for them. That lasted until one, with his behind jammed on the rails next to my ear, squirted curdled milky cow pat all down my neck. A somewhat cleaner cow product was milk. I milked the cows by hand and soon learned to be gentle. (Otherwise they kicked the bucket over!) On a cold morning at 6 am, getting your shoulder and left ear tucked into a nice warm cow is lovely. The farm cat was an undignified beggar. He would sit up like a begging dog and miaow until you squirted a teatful of milk in his face. Having washed it off - face to paw to mouth - he would repeat the performance until you or the cow tired of it. The unpasteurised milk milk went through the cooler (it was a tuberculin tested tested (TT) herd) and then into a nickel plated oval drum on trunnions, mounted like a chariot on two wheels. I delivered milk from this thing - again horse drawn - to doorsteps in Carisbrooke, using cylindrical measures to empty the milk into the jugs left outside the houses. The farmhands' bucolic humour was fairly rudimentary, practical and often over my head. They would send me to fetch the bull, a pretty docile animal, which I did by leading him on a staff hooked to the ring in his nose. He allowed this, but didn't like it much. I had to get past him in his stall to unchain his neck and he would wait until I was alongside and lean on me, all ton and a half of him. It never failed to amuse. The bull quite enjoyed it too, because the favoured way of removing him was for someone to stand the other side and fondle his testicles. He, rather naturally, moved nearer to them. I guess we were all as stupid as each other. Ron and his wife, Vi, lived in a farm cottage standing by itself in enough land to support them in vegetables, maybe half an acre. There was a pump where there had been a well, halfway down the garden. My job every morning was to bring back two buckets of water to the cottage. There was a two hole dunny in its own hut. Those buckets were emptied I know not where, but we grew some giant rhubarb. There was an old copper where pig swill was boiled. The farm's pigs were next door and Ron always owned one. I liked feeding them; they were always so grateful! The cottage larder had half a smoked pig hanging in it. We had eggs and bacon for breakfast every day. The chickens were in the garden, until they ended up on the table. Cockerels were eaten early and roasted, but chickens were killed when they no longer produced eggs and boiled to reduce their toughness. Either way, they were far more tasty than the fast-track birds mass-produced today. Having to kill, pluck and gut them was also educational. The kitchen range was banked up overnight and Vi made her own bread. We cooked breakfast on a primus stove and the mixed paraffin and meths smell can still evoke gammon rashers for me. We washed in cold water in the sink and had a bath in a zinc bath in front of the kitchen range, warming the water in the copper (a giant copper cauldron in a brick-built housing over an open fire) that usually took the washing. The washing was stirred with what looked like a milking stool on a stick (a dolly), although a more modern device was a "'posher'", a double skinned copper dome with peripheral holes, that squirted water through the clothes when shoved down hard. The radio had two batteries, a high voltage dry battery and a low voltage lead acid battery in a glass jar. The latter was replaced each week with a recharged one from the shop. Small though the cottage was, (the stairs were in a cupboard) we didn't use the front room much, preferring the cosy kitchen. I did my reading in bed - which became a life-long habit. However, most of my time was spent outdoors. Ron had a dog who was very pleased to have a boy as a companion and was a wonderful ratter in the haystacks. Animal husbandry on a farm is good training for an unsentimental relationship with other animals, but this early friendship fostered my love for dogs rather than cats, although I like them too. At eight, I was fighting a boy in gardening lesson at school, when the teacher came up from behind and clouted him. This boy was Gordon Herbert, my oldest friend, whom I've lost touch with only recently (1999) as he's in Africa. His mother, Evelyn, became a second Mum to me and she thinks of me as one of her own. She's ninety now and in a nursing home. (She has now died in 2003). Eventually, Gordon and I both passed the "11 plus" exam, which gained us entry into the local grammar school. There weren't many of us; most came from the schools on the "other ('better') side of the tracks" and the first year was a cautious exploration of each others' potential. There I met Mark Butler, an adventurous lad who my mother thought was a bad influence on me. She was not impressed when I suggested I might be a good influence on him! No doubt, she knew better. The boys from Parkway school had mostly been taught to swim, something no teacher had ever suggested for Peartree pupils, so when the grammar school took us swimming in the open air, unheated pool (53 degrees F some May mornings), I couldn't. I rapidly learned to swim long distances under water (two lengths of the pool eventually) and to dive - of course, I had to swim under water to get back to the side. This was all to avoid the indignity of spluttering and sinking when I failed to control my breathing on top of the water! The pool was cleaned on Fridays and, as the week progressed, the water got greener and so murky you couldn't see the bottom. We used to fish out the frogs that trespassed from the nearby river Lea. The better swimmers learned to life-save and naturally wanted to practice on me, a known non-swimmer. I dived off the top board, swam under the opaque water to the side and climbed out. Then I sat and watched as the lads in the middle duck-dived ever more frantically for their drowned school mate. You'd have thought they would have been pleased when they found I was safe, but there's no satisfying some people. In 1947, the winter snow came early, began to melt, then froze solid for many weeks. At 15, I cut wood and fetched coal in a sack I took to the coal yard on my bike, then walked the bike home with a hundredweight of coal balanced in the frame. Every evening after school we went toboganning on the golf course. There were several broken limbs and Mark blew himself up in the woods with a little bomb and was kept home with several stitches in his eyebrow. My clothes never got properly dry so I borrowed his oilskin overtrousers - covered in blood. That night, racing other lads, I ran into long, ice-covered grass on the sledge, face down with another boy sitting on my back. My forehead, cheeks, nose, chin and lip were skinned; all superficial, but it looked terrible. I went home and climbed in through my bedroom window so my mother wouldn't see. Fond hope! Seeing her son red raw and with clothes covered in blood (she didn't know it was somebody else's) was only one of the shocks I gave her from time to time. On another occasion I had caught a dozen fresh-water crayfish, (kind of very big black shrimps or tiny lobsters) and dumped them in the sink where they scuttled to the corners and crouched evilly. The idea was to ask my mother to cook them. She was out, so I went and read a book, forgetting all about them. She came in by the back door. Her horrified scream reminded me of what I'd meant to tell her. The end of the war meant soldiers coming home, distributing all kinds of booty, from souvenir guns to thunderflashes (heavy duty bangers that stood in for grenades in army training). We used to come up to Tewin Road from the river Mimram by the B 1000 through a storm drain - more interesting than walking up the road! - and one day Mark let off a thunderflash in the tunnel. All up the field, drain covers were lifted off as deafened boys clambered out to recover. From the age of 11 I did a paper round (you had to be 12, but I lied). The train came in at 4.30 am and we were sorting papers before six o'clock. The round was finished by 7 or 7.30, done on a butcher's bike with a big metal carrier on the front - very unstable if you wobbled. By 15, I was only doing Sundays and when I got my spaniel, he used to ride on top of the papers - even more unstable when he shifted about! Winters were horrible, wet, cold and dark, but summer mornings in Welwyn Garden City could be magical. Digswell Hill was not covered in houses in 1948 and the sun came up over a field of rabbits and pheasants. The smell of cypresses and flowers in the early morning 'before the streets were aired' as my mother used to say, made it the best time of all. Working on Eric Sherriff's farm on Digswell Hill was an introduction to more modern farming methods - still pretty labour intensive by today's working practices. Sherriff had a combine harvester which spat mangled straw out the back and poured corn into bags tied up by a worker standing on a platform at the side. These were bushel bags weighing two and a half hundred weight (280 lbs or 128 kilos) toppled into the field. Gordon and I, at 16, lifted these onto a flat bed trailer by holding left and right hands, punching the linked hands into the centre of the sack and each picking up the bottom ears with our free hands. A heave from the bottom and a push from the centre got them on board, but you were kind of tired by the end of the day. As a respite from this, you rode on the wagon to the granary and then unloaded them! You did that by yourself, untying the sack and getting it high on the shoulder so it moulded itself round your neck and head. Now all you had to do was walk up a sloping plank over the silo and, without falling over, tip it in. I remember I enjoyed that bit - it was such a relief to feel the weight empty itself out. It was as much knack as strength and one big Irishman couldn't do it. People twitted him and he said to Gordon, who weighed about ten stone, "Stand on the shovel and put your hand on my head." He then picked him up on the shovel blade and deposited him on the wagon. "That's what I can do," he said. He had been, of course, a navvy. He was also the first guy I had ever seen sink a pint without swallowing - he just poured it straight down. One night after harvest he did it ten times! Picking potatoes and pulling up brussel sprout roots was still done by hand and boys were the cheap labour (1s 9d per hour in 1947 if I recall correctly). The lousiest job was getting seed potatoes out of the clamp. The mud and rotten potatoes peeled your fingernails a long way down. This isn't retrospective boasting of how tough things were. It's just how they were and I'm glad for everybody's sake that we've moved on. One way we have moved on, not always for the better, is in our treatment of the bewildered. One man who worked for Sherriff was called 'Speedy'. He had been a soldier in a quick marching (125 paces per minute) infantry regiment in the first world war and suffered from shell shock. He had become simple and marched everywhere at high speed. On his days off, he would walk long distances and had been seen carrying his little dog back when he'd tired him out. On the other hand, he could and did put in a hard day's work round the farm. Although his work-mates twitted him, they defended him fiercely against comments by outsiders and tried to look out for him. His landlady was paid by his family to look after him and he lived as useful and ordinary a life as his inner torment allowed. Better, anyway, than being locked away or living an idle, poverty stricken existence on state benefit. | ||||||||||||||

I did fairly well academically and athletically at the grammar school, near the top of the A stream, later in the first eleven at cricket and football, captain of athletics for my house at 16 (over the heads of 18 year olds) and playing football and boxing for the local boys club. This latter was run by an ex-Commando colonel (a hero of D-Day) with strict discipline of a permissive sort. Confused? Let me explain. There were lots of things you could do at the club and, while we were blasé about everything adults wanted us to do, we were keen to play in the best teams, act in the amateur dramatics, have the best boxers, wrestlers (Cornish style), judo club; in fact, be top dog. Colonel Menday had a simple recipe. If you didn't train, you didn't play. There were no prima donnas. Nobody was indispensable or more important than the team. You didn't turn up for training? You ain't playing this week. As a result, everyone who turned up was a good team player. The high motivation did, indeed, make us top dogs very often. I played in the football team, which was good enough to win the under 18 double (League and Cup), but I couldn't train on the usual night, because I was studying for A levels at night school. I therefore trained with the boxers. They had a rule, too. Train with them and you had to box. I had a broken front tooth, due to standing in front of a boy rubbernecking as he disassembled a German pistol (a Luger). It came adrift in a rush - straight into my mouth. This meant that I started sparring fairly tentatively until I was hit in the mouth and bled. After that, I couldn't be hurt, I was concentrating too much on getting my own back. It taught me two, no three, things. To lose my fear of being hit in the face. To control my temper (you got hit a lot more if you were careless, some of these guys were good). And not to go on boxing. My brains seemed quite loose inside my skull and blows to the head left me with a headache. I switched to judo and wrestling instead. By this time, we were a gang of three; Gordon, Mark Butler and me, three boys who went everywhere together from the age of twelve to sixteen, when girls at last began to intrude. I did my homework in lodgings, with two smaller children from our landlady's family (the Rees's at 17 Bythe Mount) around and the radio on all the time. ITMA, standing for It's That Man Again, with Tommy Handley, was the comic programme we all listened to, although Much Binding in the Marsh ran it a close second. A great deal of the music I absorbed was classical, with the result today that I love many pieces of whose titles I am ignorant. After the war, my father sold the house (No 44) in St Georges Road Hastings for a relative pittance and I was somewhere between thirteen and fourteen when we moved into our rented home in Welwyn Garden City. We moved all our possessions at last into our new house. A giant bookcase arrived, with crate upon crate of books to fill it. My father's taste was catholic enough, but his library extended beyond that. He used to go to book auctions and shift books he wanted into one lot - then bid for that. However, he could never bring himself to throw away the other books and a weird and wonderful collection they made. I never understood 'Inman's Nautical Tables' (for 1899) until I did navigation classes in my 40's! At seven, I had been learning to play the mandolin, a beautiful deep bodied instrument made from strips of different coloured woods. When that resurfaced from the attic, the glues had failed and it had opened out like a tulip. To my lasting regret, I never learned to play a musical instrument after all. My school work, homework, paper round and weekend work on a local farm, (which also involved dog, ferrets, nets and rabbits in close proximity) used up a lot of my time, but I still patronised the library as well as the Beano, Wizard and Hotspur comics. Lord Snooty and his friends, Pansy Potter, Desperate Dan and his cow pie, and an athlete called Wilson, are all characters I remember. The comic book heroes had short, broken noses and enormous craggy chins. I didn't and despaired of anyone thinking me attractive. Who'd want to be 15 again? The library books included primitive (by today's standards) science fiction and I graduated to Astounding - the most famous of sci-fi magazines - E Doc Smith, Asimov and Heinlein as some of the authors.

The rabbits we caught we sold to the local butcher for half a crown (or three and six if we skinned them). We had to leave the kidneys in; cats' kidneys lie differently from rabbits' - and cats taste different, too! We skinned the rabbits country style. Slit the rabbit from anus to sternum, shake out the guts; slide your hand under the skin round the back and pull the rabbit inside out. Cut off feet and head, discard, hand carcass to suspicious butcher. We also had slings - two leather bootlaces and a leather pouch for a pebble. They sent the missiles much further than a catapult and we grew quite accurate with them. Mark even hit a grey squirrel, which I took home and skinned to try and cure the pelt with alum. It didn't work and the pong was horrendous. However, my cocker spaniel had a kennel for the summer and I bequeathed it to him for a doormat. He loved it and lay in his kennel with his nose on the fur dreaming doggy dreams of chasing game. But back to my father's books. I was adolescent, with new emotions fermenting inside me. Half the time I wanted to be a very parfait knight, doing brave deeds for at least one pig-tailed maiden in my class (and I've every reason to believe that in those far-off days they were indeed maidens) and the other half wanting to have my wicked way with them (except I didn't know the way). Into this mix poured the ideas of a galaxy of authors. I had two books stuffed down the settee, one in the loo, two on my bedside table and often carried one about. We didn't have television and the radio didn't distract me. I could pick up any book and, in half a page, remember what it was about. It was a wonderful time. Find a new author, be entranced; turn to the title page and see that he's written ten more books! Pickwick Papers, all of Rider Haggard, Conan Doyle, Edgar Allan Poe, Wodehouse, W W Jacobs and that unsurpassed storyteller, Kipling, were my constant companions. Old-fashioned? Well, yes, but I've reread many of them with much pleasure, a different understanding and getting something new from them as my own experience has grown. In times of trouble, Wodehouse in particular has been a refuge and escape route. Kipling never ceases to please my sense of prose rhythm and delight in the "diversity of Allah's creatures". My love affair with books invaded my unconscious. When playing football, I was tripped and kicked in the head. One second I was running hard and about to pass the ball, the next I was sitting comfortably at home reading a book and just going to turn the page to some marvellous denouement. Then someone stuffed a cold wet sponge down the back of my neck. | ||||||||||||||

|

At sixteen, two weeks before I took my school certificate exams, life stuck a cold sponge down our family's neck. My father died from a thrombosis while at work. (Someone asked him to help shift a piano. He was 67 and had high blood pressure - and there weren't any effective treatments in those days). My mother and I went to see him in the morgue, with me unaccountably afraid. This was my dad, but also the first dead body I had seen. It struck me then and since, that the dead clay is indescribably empty. The reality that was the person is elsewhere. I cannot doubt that there is more to the world than our five senses appreciate. I suspect, with Haldane, that not only is the world queerer than we imagine, but queerer than we can imagine. I am, therefore, agnostic, but hopeful. It seems stupidly egotistical to believe we shall survive in any form we could recognise, but the universe appears to be ordered in a coherent way and what more can you ask? Certainly time is not as it appears to our limited senses. We feel no great surprise when past events return to our minds so vividly that they seem "real", but few think that we can see the future. To my chagrin and sorrow, I have done so and I hope never to again. My mother, who said she was the "seventh child of a seventh child" - for those who set store by such things - saw my brother standing at the mouth of a railway tunnel waving good-bye to her and turning to walk down the tunnel. This was shortly after he was posted missing and, you would say, an obvious metaphor for death. After the war, she heard that he was aboard a train that was bombed as it entered a tunnel in France. Coincidence? Well, maybe. I have since researched the action from records of the 7th Sussex regiment in Chichester and my brother died either in the train or in the battle that followed. There is no record of his surviving to go to hospital or to join the 'death march' that the regimental prisoners underwent to Poland. The record that would determine what his fate was must be the roll call I now know was taken after the bombing and before regrouping in defensive positions on a hill. That information is in the War Diaries at Kew - something yet to do. See In Memoriam for further information. Thus ended my childhood. We had no pension from my father's job, little capital from the sale of his defunct business and only my mother's wage to keep us. At sixteen, I was the man of the house. I was a fortnight away from taking the matriculation exams that might mean my assisted entry into University. The school suggested that I delayed until September, but I saw no point. The work would distract me from my sadness, my revision had all been done and Yorkshire parenting meant you didn't give up just because things had become difficult. In fact, I did well (four distinctions and four 'credits' from eight subjects) and the school believed that I could, at eighteen, get a State Scholarship to University. When my mother pointed out we couldn't afford it, the headmaster lost interest. Is that unfair? Probably. I don't suppose there was much he could do for me anyway. So I took a job and went to night school. I earned £2 10s and gave my mother £2 5s of it. But, I had a .410 shotgun and a cocker spaniel (which my mother bought me as a reward for matriculating), a farm where I sometimes worked at weekends, a countryside to roam and two friends. I was rich. One of my friends, Gordon, had a bull terrier that, in its adolescence, terrorised the other dogs, the milkman, the postman and anyone nervous. He never bothered my dog, but acted as his protector. As he grew to maturity, he no longer fought rivals, merely shouldered them contemptuously into the gutter. If any dog was barmy enough to raise its hackles and walk stiff-legged around him, he never joined in these preliminaries. He just grabbed the dam' fool by the throat and tried to strangle him. There was just one way to get him off; stick a pencil up his bum. Then take your hand away as quick as you like. No, quicker than that! We walked all over Hertfordshire, rough shooting, birds-nesting and gathering things to eat (rabbits, pheasants', partridges', ducks' and peewits' eggs, wild raspberries, strawberries and blackberries) as well as scrumping apples, plums and pears. The most unpleasant thing we ever ate was a hedgehog - and that's all the fault of reading comics. Self-reliant heroes lived off the land and adopted gipsy techniques, like baking hedgehogs in their prickly skins wrapped in clay. When the clay baked, cracked and fell off, so the stories went, it took the prickles with it, leaving delicate, steaming flesh, ho hum. The bull terrier could kill hedgehogs by clawing them open when they rolled up, and he did so to this one before we could stop him. We now had a freshly killed hedgehog we could gut with a penknife, some mud and matches to light a fire. No sooner said than done, but with boys' impatience, not done enough. The mud fell off early on - what did we know about the difference between mud and clay? - and we tried to eat half raw meat. The best you could say was there wasn't much of it and none of us went back for a second bite. Gordon also kept a pig in what had been a chicken run in his garden. The Government would slaughter the pig for you and give half of it back (I think this scheme still endures) once you had reared it to maturity. However, what restrained chickens was no match for a 20 score pig (a score is 20 pounds or 9 kilos) and it often escaped. We have chased it down suburban streets in the company of neighbours, strangers, police and probably Uncle Tom Cobley an' all, more times than I care to remember. The old joke about someone who's bandy is "that he couldn't stop a pig in a passage". I'm here to tell you that you can't even if you're not. It just knocks you flat and runs over you. When Gordon's father kept chickens, the eggs were preserved, (this was wartime, remember) before domestic freezers or even fridges existed, in a bath of isinglass, which sealed the pores in the shells. He also kept ducks, which were killed for the pot by hanging them up by their feet and cutting the artery in their necks to let them bleed to death. We were, I suppose, vandals. There were too few of us to damage the countryside permanently, but we did our best. We had birds' egg collections; good ones, too. We stole baby birds out of their nests and hand-reared them; for instance, wood pigeons (ugly little blighters before they're fledged) and a beautiful little owl. We never caged them and they all flew away eventually. It never occurred to us that we might be wrecking their chances of survival in the wild. They got their own back on me. I climbed a pine tree to a nest in a strange position, only to find it was just a blackbird's. One egg, cold and abandoned, so I put it in my mouth to keep it safe while I climbed down. Pine trees have no lower branches, just the dead twigs where they have been. The topmost of these broke under my weight, so did the next, and the next . . . . I came down with a rush and a heavy jolt at the bottom, when the ground broke my fall. My jaws clamped tight - and the egg was addled. The awful taste lasted an awfully long time. The little owl was wonderful. We shot sparrows for him and fed him by hand. He would fly down and perch on your finger, gripping with talons that sometimes drew blood. When he blinked open his eyes, it was like two furnace doors revealing the orange fire within. One day, he flew away. We carried knives and axes with us everywhere. A favourite game was to climb a sapling maybe 20 to 30 feet high and everyone else would chop it down as fast as they could. You were chicken if you didn't climb (and that was intolerable) and the trick was to be really brave. Once at the top, you should sway the tree as hard as possible. Then the trunk splits early under the axe blows and you come down slow and easy on the spring. Be timid, and your so-called friends have chopped right through before you can cry fainits and you come down with a rush. We also, in common with many other groups of boys, built a camp in a giant pile of concrete building blocks between the ICI factory and a railway siding (off the old Hertford line, now dismantled). These blocks were oblong, with two square holes from top to bottom. Hollowing out the pile, roofing with corrugated iron and using the hollow blocks as chimneys made wonderful camps. There was even a heap of coal in the siding, which we stole from time to time. (Thank goodness for the statute of limitations!) To light the coal, we needed wood. Tar soaked wood was readily available. It came in the form of small blocks that held the railway lines to the sleepers. The rails in the siding became decidedly wobbly. We co-existed fairly peaceably, but we couldn't resist the occasional tweak. A favourite, on the way home, was to walk along the top of the pile - it really was enormous - and pee down a smoking chimney, stuffing a sack down immediately afterward. A good way to improve your sprinting fitness! But I hadn't finished with the pig. When the lorry came for him, the driver wanted nothing to do with getting him on board. Two sixteen year old lads couldn't shove it up the ramp and we were getting pretty sweaty, but otherwise - nowhere. Along comes an Irish feller. "Are yer tryin' to get the pig in th' lorry?," he says. We look at him pityingly. "Get us a stick," he says. Gordon fetches him a stick. He grabs the pig by the tail and positions it at the bottom of the ramp. Then he whacks it behind the ear with the stick and heaves upward on the tail. "Yip!" he yells and with a scramble and squeal the pig's suddenly in the lorry. He hands Gordon the stick. "Many's the pig Oi've taken to market in Dublin loike dat," he says and strolls off, pleased as Punch. Around this time, I started to go riding from a stables near old Welwyn at the Frythe. We paid to hack, so got no lessons but, being boys, we galloped anyway and, being lucky, didn’t kill ourselves. I rode like a jockey, with shortened stirrups and standing clear of the saddle. I finally learned to ride properly on a post trail holiday in Northumbria many years later. I also used to go to Queens ice rink in Queensway and sometimes to Streatham. Again, we had no lessons and probably looked naff, though bold and quick! One last adventure before girls caused us to wash and shave and feel funny. The local sewage farm produced activated sludge and, incidentally, wonderful wild strawberries; ask not their provenance. This sludge was led to a low-lying field by the river Mimram and allowed to settle, the water running over a weir into the river, where we paddled a Mosquito drop tank (a wing petrol tank from a WW II fighter-bomber) as the most unstable boat I have ever been in. An old oak in the field had raised the ground level so it formed an island where swans had made a nest. The swans were away; were there eggs? We had to find out. We built a rickety raft - and I mean rickety. It wouldn't hold three of us so we drew lots. I lost (or did I?) and stayed on shore. Halfway there the swans came home; not swimming, but flying hard, feet paddling the water, wings beating and hissing alarmingly. My companions turned tail and paddled for shore even harder. So hard that the raft disintegrated under them. That left them wading in knee-deep sludge. As they dried out on the way home, I walked further and further away from them. Their mothers weren't pleased. Around this time I went with five other lads on the Broads. They were all older than me and only one of us had ever sailed before (and it wasn't me). It became the kind of holiday you should never try to repeat. It was such enormous fun that any attempt at repetition would be bound to disappoint. The two boats came back rather the worse for wear and we came back constipated. We didn't know how to cook. The three of us on our boat had 48 eggs between us in a week. We even had fried eggs with stew. One attempt to make porridge ended in a kind of glue that persisted in the saucepan even after having been towed behind all day. In those unregenerate days the toilet on board emptied straight into the water and the pumping system was shared with the bilge pump by switching a water valve. One of our number discovered that by leaving the valve in a halfway position, the river water could find its way back into the toilet. . . . . We were supposed only to cook at anchor, since the cabin roof was lowered while sailing and there was little head room. We found we could sail on if the cook crouched on the toilet and fried up on the galley across the companionway. However, with the valve halfway open, going about on the other tack dumped at least three gallons of water into the cook's trousers - a joke that could only be played once! We got lost in the reeds, we nearly sank one boat in a water fight, we rammed each other and were frightened silly by a thunderstorm. (The countryside was as flat as a turd from a tall ox and our masts were the sharpest lightning conductors around). The ramming broke a strut that raised the cabin roof on our friends' boat above the toilet. Going to the loo became far too uncomfortable, so they used to wait for darkness and crouch over the side of the boat (yes, yes, but they were young males, what do you expect?). What they didn't expect was to be lit up incandescently by our nice new flashlight! Very constipating. On the last day, we ate up the remains (or, rather, one of us did). Like, a tin of sardines, some rather old cheese, various odds and ends and, right at the back where it had got lost, an open and rather sugary tin of condensed milk. We hitched home and one of us (yes, that one) had to ask the lorry driver to stop for a minute to himself. Getting back in, he rather shamefacedly suggested that the diesel fumes had upset him! I hitchhiked to the Peak district with this same Harry Wray to go potholing. I was 16 and Harry was 18. That my mother allowed me to go says something about her trust in my self-reliance and more about how safe the world seemed to be for hitch-hikers. We camped in a field in Castleton, where two horses who shared the field with us indulged in 3 am canters past our tent. Harry sat up to fend them off, but I was too tired to care. We went down a Blue John mine and turned round so many times, looking for Blue John to chip, we forgot which way we had come in. Fortunately, our random choice of exit turned out to be correct. Later we went potholing and took a piece of twine (shades of Ariadne) and candles. Quite soon, we lost the twine down a hole, but went on anyway, in the company of a lad on a day out from Sheffield in his best suit. We came to a point where the path disappeared into a hole in the cave floor. Candles did not illuminate downwards, but pebbles dropped down appeared to hit something almost immediately. I lay on the ground with my head and arms in the hole, while the Sheffield lad sat on my feet. Harry went down into the hole until he was hanging full stretch from my hands. He still couldn't touch the bottom, but said to me, "Let go, it can't be far!" I didn't want to, but when he didn't return my grip, he just slipped from my grasp. He turned out to be about 4 inches above the ground, so we all went down. On the way back, we stood in turn on our new friend's shoulders to climb through, then Harry sat on my legs while I hung backwards down through the hole from my knees, thus letting the last man swarm up me. When we emerged into the open air, we realised just how much muddy water had soaked into us. The nice new suit had footprints all over its shoulder pads, with matching patches randomly, but liberally, distributed. The young man didn't seem bothered, but went off thanking us for an interesting day. We went to find a river to wash in. The one we found had a notice we didn't see till later. It said, "This river comes from Peak Cavern and is 44 degrees F all the year round." One day, a chap in a caravan in the next field came and asked us if we could drive, because his dog had gone hysterical in the heat and he needed to get it back to Sheffield. We couldn't, but we offered to hold the dog, just about the biggest Alsatian either of us had ever seen. During the journey, the dog was obviously distressed and incredibly restive, nearly smothering us both, so we opened the window to give it air. It immediately made valiant efforts to climb right out, foiled only by our winding the window back up when it was already halfway out. It was a dickens of a job to recover it inside. The guy gave us a lift back and bequeathed all the food he hadn't eaten to us as a reward. I think he must have been a black marketeer. We ate better than we had for years! I think I must be condensing the time-scales here, or how did I find time to start taking girls to the pictures? The days must have been longer then. College and homework took up many evenings, but girls and rising sap meant revision taking a back seat many a time. Motorbike building, old car maintenance (none of them belonged to me) and football competed with the young Adam and often lost. I went out with one girl, just once, before she threw me over for some other acned oaf, but this meant I was introduced to her best friend, Joan Haydon, to whom I eventually got engaged and later married.

A steady girl-friend meant I gave up football in favour of tennis, swimming and dancing, where you got to share with the girls and even, the foxtrot, waltz and quick-step being what they are, hold on to them. Another reason for giving up football was that the bruises were lasting longer than a week, so new ones began to grow over the old ones. At 18, someone headed me instead of the ball, and I lost the broken front tooth that had just been finally fixed. Penicillin would have saved it by curing the abscess that formed, but antibiotics were then only available for life-threatening illnesses. Time to stop. | ||||||||||||||

I had found a job in the laboratory of a local pharmaceutical company (Roche Products) and attended college on an evening and day release scheme in an attempt to obtain a degree in chemistry. They paid me £2 l0s (£2.50) a week and I gave my mother £2 5s (£2.25), leaving 5 shillings (25p) to spend on myself - but not all at once! As a lab assistant, I learned to handle dangerous chemicals, but the degree of protection afforded the staff was poor by today's standards. The long-term effects of many common solvents and reagents were simply not known or, maybe, disregarded. We evaporated benzene, toluene, chloroform, ether and carbon tetrachloride in the open lab (and three at least out of those five are carcinogenic). Research is also like being a test pilot; you think you know what will happen, but you can get very surprised. We were making synthetic curare-like compounds, to use as muscle relaxants in surgery and the homologues were getting more toxic as we added longer side-chains. I was told to complete the series by making the methyl version (the lowest in the series, which we had missed). I did, then dried the powder and scraped it into a bottle in the open lab. Within 5 minutes, my throat was paralysed and I couldn't speak. 30 minutes later, I was OK again. When tested, this material was so poisonous they couldn't find a low enough dose that didn't kill all the mice it was given to. Nobody ever made it again. On a lighter note, we had two middle-aged women who washed up the glassware. What detergent wouldn't remove, they used mixed solvents on. (Something else that would never be countenanced today). In pouring the solvents back into the bottle from a bowl, one woman spilt the liquid down the front of her dress. She came red-faced and furious into the lab steward's office. "What are you going to do about this?" she yelled, holding up a large circle of elastic attached by slimy pink ropes to two smaller circles below - the remains of her viscose directoire knickers. What we did do was fall about laughing helplessly. The lab I worked in made riboflavin (one of the B vitamins) by a fermentation process, using molasses as a culture medium. This came in big square tins and all the lab assistants vied to spoon out the residues from the tins. This was 1948 remember, with all of us starved for sugar and luxuries like sweets. The work was also dangerous. One lad breathed in hydrogen cyanide and was given the antidote, itself incredibly poisonous. He eventually died in hospital - from the antidote, it was rumoured. One beautiful experiment (not authorised) was to blow bubbles filled with hydrogen and light them with a taper. The hydrogen burned at the interface with the oxygen in the air, producing a wonderful ball of quiet flame rapidly reducing in size until it disappeared with a little 'pop!'. We rang the changes by filling a rubber balloon with hydrogen and popping that with a lighted taper. The collapse of the balloon mixed the hydrogen violently with the air, producing a horrendous bang and a large pressure wave.

| ||||||||||||||

|